THE POTENTIAL ORWELLIAN HORROR OF CENTRAL BANK DIGITAL CURRENCIES

July 13, 2021 in News by RBN Staff

source: blacklistednews

Published: July 12, 2021

SOURCE: ADAMS ECONOMICS

-

86% of central banks are actively researching the potential for CBDCs;

-

60% were experimenting with CBDC associated technology; and

-

14% were deploying CBDC pilot projects.

-

Publicly-issued currency by central banks in the form of physical cash (coins or banknotes) and central bank reserves which constitute legal tender (i.e., form of currency or money which are legally recognised as a means of payment to settle financial obligations such as debts, taxes, contracts, legal fines or damages)[6]; and

-

Privately-issued currency by private commercial banks, telecom companies and specialised private payment providers – that is, digital forms of legal tender that are issued and held by non-government financial institutions (e.g., bank deposits or balances held in payment systems such as Paypal or Alipay).

-

managing customer facing activities – i.e., providing retail banking services such as payment accounts, authorisation, clearing, settlement and dispute resolution;

-

developing and releasing innovative payment products which more efficiently facilitate commerce both domestically and internationally; and

-

ensuring compliance with anti-money laundering (AML) and know-your-customer (KYC) obligations.

-

Faster private sector payment systems – payment system providers such as Alipay are able to process 120,000 transactions per second, which is almost double the processing speed of credit card companies (such as Visa) and are much faster than traditional processing times of commercial banks[8].

-

Retaining sovereign control – the emergence of private sector payment systems means that central banks contain less control of the money supply thus rendering monetary policy less effective as an economic policy tool[9].

-

Financial stability – the potential failure of a private issuer of digital currency could disrupt the payment system and destabilise either the financial system of a nation (and even the global economy, if significant enough)[10].

-

Financial inclusion – the rise of narrow and private money networks could exclude segments of an economy’s population from enjoying digital financial services or being able to consume particular goods and services[11] (sometimes referred to as ‘unbanked’ customers).

-

Zero-lower bound interest rates (i.e., negative interest rates) – the existence of physical cash results in the severe curtailment of the ability of central banks to lower official interest rates below the zero bound (i.e., implement negative nominal interest rates) given the risk that citizens are likely to withdraw from the financial system by hoarding physical cash if negative nominal interest rates are implemented[12].

-

Enhancing the effectiveness of fiscal policy – the existing dual-currency system makes the deployment of fiscal stimulus payments (whether one-off payments or continual payments such as Universal Basic Income or UBI) highly cumbersome and inefficient for governments who deal directly with citizens or who issue payments through financial intermediaries[13].

-

Declining use of physical cash – the declining use of physical cash in particular economies coupled with the widespread use of alternative digital currencies by the private sector could undermine market competition – for example, where a company uses their dominant position in one industry/sector to control payments and competition in other entities (or sectors)[14].

-

Cyber risk – with “Big-Tech” providing payment options through cloud-based technology, such technology presents risks to wholesale and retail market participants which may undermine confidence in digital finance as a means of facilitating transactions and storing value.

-

settling wholesale and retail level transactions at processing speeds on par with private payments systems offered by “Big-Tech” firms (such as Facebook or Paypal) but at a much lower per-transaction cost, thus arguably generating a rise in productivity;

-

providing a resilient and universally-accepted form of digital payment;

-

preventing the leakage of the money supply away from central banks towards private payment systems, thus ensuring central bank relevance in the monetary system and that monetary policy retains its policy effectiveness;

-

allowing central banks to intervene and stabilise the payments system and by extension the financial system in the instance where private sector failures were to occur;

-

providing ‘unbanked’ citizens with the opportunity to participate in the digital economy;

-

providing central banks with greater policy flexibility to implement negative nominal interest rates (i.e., official interest rates below the zero bound) without the risk of cash hoarding; and

-

making fiscal policy transfer payments (including stimulus payments) more efficient by allowing governments to send central bank issued digital currency directly to the retail accounts held at central banks in the instance where a retail CBDC exists.

-

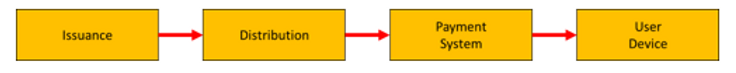

the issuance of CBDC (including what will be issued, how and in what quantity);

-

how the CBDC is then distributed through an economy;

-

what payment system will facilitate the widespread adoption of the CBDC; and

-

how the CBDC will/can be accessed by users (i.e., the user device).

-

Wholesale vs retail CBDCs – Wholesale CBDCs refer to those that solely deal with wholesale transfers and payments between central banks and commercial banks and other large non‑financial institutions. Retail CBDCs are instead digital forms of centrally-issued currency which can be accessed and used by the general public.

-

Centralised vs distributed – a distributed CBDC means that the digital currency (including the its electronic ledger) is able to be accessed and used across multiple devices that are communicating and co-ordinating over a network.

-

Account-based vs token-based – Account-based CBDCs are those held in individualised accounts at the central bank. Token-based CBDCs are instead units of digital currency issued by the central bank that are recorded on the blockchain and stored in digital wallets.

-

Interest-bearing characteristic - CBDCs that are held in accounts at the respective central bank and have the ability to generate interest income, or may even be indexed to an aggregated price index[15].

-

Disintermediation – some have argued that account-based retail CBDCs whereby citizens have the ability to deposit their currency holdings directly at the central bank may divert essential funding sources of capital away from commercial banks thus undermining their ability to issue credit with adequate capital reserves.

-

Privacy – retail and account-based CBDCs means that governments and central banks can monitor the financial transaction and economic affairs of individual economic agents, thus eliminating the benefits of privacy and confidentiality which physical cash affords individual economic agents[16].

-

Loss of economic freedom – beyond the privacy concerns raised above, retail-based CBDCs pose risks to the economic freedom of individual economic agents given that central bank officials will have the ability to impose conditions on account holders.

-

Technology risk – the technological infrastructure underpinning CBDCs and their operational performance may experience technical shortcomings which can hamper their effectiveness in facilitating commerce and economic activity. This risk may include cyber hacking which leads to the theft of CBDCs.

-

Miscalibration of government or central bank involvement – ill-conceived interventions by government or central bank officials may result in negative consequences either for specific market participants or for the broader economy.

-

Runs on commercial banks – as noted by the IMF in June 2020[17], retail CBDCs have the ability to facilitate a run on the deposits of commercial banks during periods of financial panic and distress resulting from a transfer of funds held at commercial banks to CBDCs.

-

Cross-Border interoperability – this may include multiple national level CBDCs unable to effectively interact and communicate which may hamper cross-border financial flows and harm the ability to invest and trade. Thus, if seamless interoperability is not achieved, this may result in harmful international spill overs[18].

-

the monitoring of all economic and financial transactions within their jurisdiction;

-

the collection of bulk data to be then used for other purposes, including law enforcement, the targeting of political enemies and the silencing of political dissidents;

-

the implementation of social management policies such as social credit scores – i.e., imposing financial penalties or constraints on citizens who engage in activities that are disapproved by government agencies or authorities;

-

the imposition of financial costs (e.g., fees) on using physical cash or exchanging physical cash for CBDCs. Such costs do not necessarily require the outright elimination or prohibition of physical cash by governments and central banks[19];

-

governments and central banks to direct financial capital into asset classes preferred by policy makers (such as government bonds) or to divert capital from asset classes they disapprove;

-

the compelling of economic agents (businesses and individuals) to consume particular goods and services preferred by policy makers;

-

governments and central banks to impose particular conditions in the case of fiscal stimulus lump-sum payments, such as imposing time limits on when an allocation of digital currency must be spent, otherwise the digital currency may be electronically withdrawn from circulation; and

-

the confiscation of CBDCs held at the central bank, either through negative nominal interest rates, specific fees and charges or by outright confiscation (such as through haircuts or deposit “bail-ins”).

-

the CCP to more effectively impose party discipline within China; and

-

more effective implementation of China’s social credit score system[20].

-

the stability and orderly functioning of the traditional financial system; and

-

the ability of central banks to implement effective monetary policy,

-

existing structures of economic power;

-

institutional arrangements; and

-

cultural practices