A small Oklahoma city elected a white nationalist. Now residents face a decision.

March 14, 2024 in News by RBN Staff

via: MSN.com

By NBC News

ENID, Okla. — The photo of Judd Blevins was unmistakable.

In it, Blevins, bearded and heavyset, held a tiki torch on the University of Virginia campus, on the eve of Unite the Right, a 2017 coming-together of the nation’s neo-Nazi and white supremacist groups.

Connie Vickers had found the photo online along with others showing Blevins marching alongside an angry mob — a crowd of men recorded throughout the night spitting and shouting “Jews will not replace us!” Vickers had it enlarged at a local print and copy shop. On a January night in 2023, she and Nancy Presnall, best friends, retirees and rare Democrats in a deeply red Oklahoma county, brought it to a sparsely attended forum where Blevins, a candidate running to represent Ward 1 on Enid’s six-seat City Council, was making his case.

They had hoped to get a question in while Blevins was on stage, but settled for confronting him after.

For more on this story, watch NBC’s “Nightly News with Lester Holt” tonight at 6:30 p.m. ET/5:30 p.m. CT.

Hearts pumping, Presnall and Vickers approached the 41-year-old former Marine. From a kitchen trash bag, Vickers pulled out the blown-up photo of Blevins and asked about his ties to white nationalists.

As his campaign manager whisked a red-faced Blevins away, Vickers and Presnall followed, yelling, “Answer the question, Judd!”

“He ran away from two little old ladies,” Presnall recalled.

Two weeks later, on Valentine’s Day, Blevins won his race, unseating the Republican incumbent, widely viewed as a devoted public servant, who died from cancer later that year. Voters seemed to appreciate Blevins’ bio: a veteran who’d served in Iraq and who’d worked a manual job in Tulsa before moving back to his hometown to take over his father’s roofing business. Blevins described himself as a man of God and extolled the city as a place where “traditional values” remained the norm.

The message resounded in Enid, a city nearly 100 miles north of Oklahoma City with just over 50,000 people. In 1980, more than 90% of the area’s residents were white; now less than 3 in 4 are. Enid is both one of the country’s most quickly diversifying places and one of the most conservative, where residents describe the ever-present whirring of jets from nearby Vance Air Force Base as “the sound of freedom.”

It’s not clear how many voters knew about Blevins’ white nationalist ties. There was an article in the local paper, which Blevins labeled “a hit piece,” but beyond the confrontation with Vickers and Presnall, it just wasn’t talked about. Blevins wasn’t asked about it at campaign events or forums and his opponent never brought it up.

But a white nationalist campaigning for office is one thing; his election is another. And Blevins’ win didn’t sit well with many in Enid. It marked the beginning of a fight to expel Blevins from the City Council — a fight for the very soul of Enid that would unite a coalition of its most progressive residents, divide its conservatives and show the power of community organizing.

Over the next year, grandmothers would be branded antifa radicals, local organizers would be accused of attempted murder, and a national white power movement would stake its claim on the City Council. And for a growing number of state and local governments confronting extremism in their ranks, the outcome of that fight — Blevins’ recall election on April 2 — will serve either as a model or a warning.

Blevins has declined multiple interview requests. (In response to questions about his white nationalist ties, he told a reporter, “I hope you find God.”) So when, how and why Blevins got involved with a white supremacist movement may never be known.

What is clear is that from at least 2017 to 2019, Blevins was an active leader in Identity Evropa, one of the largest among the white nationalist and neo-Nazi groups that collectively made up the alt-right.

In public, Identity Evropa eschewed the racist label, opting instead for sanitized descriptors like “identitarians” who were focused on “preserving Western culture.” But privately, in secret meetings and internal online chat groups, members were clear about their motivations and beliefs. In posts that praised Nazis, denigrated racial minorities and professed the superiority of white people, pseudonymous Identity Evropa members spoke candidly about their goal of normalizing racist ideologies and infiltrating conservative politics.

As the group’s Oklahoma state coordinator, Blevins flyered its major cities and universities with his group’s white nationalist propaganda, organized and participated in banner drops over state highways, and recruited, interviewed and accepted new members into the fold. Blevins marched at the tiki torch rally alongside hundreds of men in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017 and the next day at Unite the Right, where he carried the original Oklahoma flag.

Blevins remained active in the group even after the rally ended in violence, with beatings of counterprotesters and the murder of a 32-year-old paralegal and civil rights activist. In a 2018 podcast, Blevins, who went by the online moniker Conway, talked about his passion for recruitment.

“As we like to say in Identity Evropa, there’s nothing you can do to stop us,” Blevins said.

Most of this was reported by left-wing news outlets three years before Blevins ran for office.

In March 2019, Unicorn Riot, a progressive media collective that covers social movements, published Identity Evropa’s private chats, which anti-fascist researchers and journalists then used to identify people who planned and attended the Charlottesville rally: police, teachers and members of the military among them. One group matched Conway to Blevins based on photos, biographical details and Conway’s disclosure that he would be marching at Unite the Right with Oklahoma’s original flag. The progressive news outlet Right Wing Watch published an article soon after outing Blevins to a wider audience. NBC News verified this reporting and unearthed more evidence of Blevins’ white supremacist identity, including posts, photos and a podcast appearance.

After his unmasking, which included antifa activists posting photos of his family and the Tulsa lawn-care business where he worked, Blevins shut down his social media accounts.

In one of his final messages in the Identity Evropa internal chat, he said he was moving back home, and, in one of his last tweets, he hinted at wider ambitions.

Under another pseudonym, Blevins posted that “our guys” — meaning fellow white nationalists — should be supported in pursuing local elected office “such as city council.”

“Basically positions where one can fly under the radar yet still be effective,” Blevins posted.

Back in Enid, Blevins kept a low profile, fixing roofs for his dad’s company. In 2022 he announced his candidacy, and it didn’t take long for the local newspaper to get wind of Blevins’ past.

The Enid News & Eagle doesn’t wade into controversy often — aside from its endorsement of Hillary Clinton in 2016, a gut punch to the city’s conservatives that led to a flood of canceled subscriptions. Most stories are of government meetings, high school sports and features about local heroes and businesses. Cindy Allen, a former editor and publisher, and a conservative Republican herself, knew people in Enid would be suspicious of the left-wing outlets that first reported on Blevins, so over five weeks, she and a reporter retraced Right Wing Watch’s steps and then published a front-page exposé.

It’s unclear how many people in Enid read the article. “Let’s be honest,” Allen said. “The readership of newspapers is a lot lower than it used to be.”

Blevins declined to be interviewed, but gave the paper a statement alleging that leftists backed by a “George-Soros-funded” media outlet were behind a campaign to brand him a Nazi.

Around the same time, Connie Vickers was conducting her own investigation. She pored over Blevins’ old posts, collecting the ones where he mentioned Hitler admiringly and joked about wearing a swastika armband. Vickers scoured news footage from Charlottesville for Blevins. She collected screenshots and forwarded them to her friend Nancy Presnall. She made her sign. Armed with that evidence, representing the Garfield County Democrats, Presnall began speaking at City Council meetings. At a meeting in January 2023, a week before the candidates’ forum, she warned about Blevins’ candidacy and support, calling it “an underlying evil that is coming into our town.”

Blevins won by 36 votes in an election where 808 people, less than 15% of the ward’s 5,600 registered voters, came out — a dismal turnout on par with municipal elections across the country.

The credit — or the blame — for Blevins’ victory depends on whom you ask. Some say it was name recognition; Blevins shares a last name, but is no relation, to the beloved owners of the only locally operated grocery store, Jumbo Foods. Most credit a local conservative activist who managed his campaign and his supporters from the Enid Freedom Fighters, a Facebook group-turned-political force that warred against mask mandates and then certain library books. Blevins’ campaign materials, which leaned into this hard-right Republican identity, were unprecedented in an Enid City Council election — which had always been nonpartisan.

Blevins’ win represented the kind of quiet progress white power groups had been preaching. As the alt-right splintered after Charlottesville, leaders urged their members to log off the internet, remove their masks and get involved in the political establishment.

“The Republican Party is comprised largely of white, aging baby boomers,” white supremacist James Allsup told Identity Evropa conferencegoers in 2018. “As baby boomers age out, the positions they hold will become vacant all throughout society and somebody will have to fill them.”

Most of the avowed white supremacists who ran for office in 2018 lost. Increasingly, though, far-right activists and extremists, including those espousing white supremacist beliefs, are faring better. In 2022, the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism identified more than 100 right-wing extremists running for office nationwide. Nineteen won.

The fallout from these local elections has rocked communities from Florida to Idaho. Christian nationalists in Ottawa County, Michigan, pushed out their moderate Republican counterparts in 2023 and took over a county board. The same happened with far-right activists the year before in conservative Shasta County, California.

In Enid, Blevins’ election galvanized an opposition. In March 2023, around 100 people, including Vickers and Presnall, met at a community center. By the end of the evening, they had formed the Enid Social Justice Committee and decided on its first order of business: recalling Judd Blevins.

The group elected a chair and a vice: Kristi Balden, a 58-year-old mother of three, easily spotted in Enid with her pink hair and white cowboy boots, and James Neal, 48, priest of a small inclusive Orthodox Catholic parish and local firebrand known for his flowing garments and embrace of the LGBTQ community.

They created a Facebook page and urged followers to sign an online petition. They launched a website that laid out the evidence against Blevins. They made buttons and T-shirts emblazoned with images of raised fists, and hosted grill-outs, bake sales and protests.

When former state Sen. Jake Merrick hosted Blevins on his Freedom 96.9 talk radio show in March, he noted Blevins was “under attack.”

“They would like to see me apologize and denounce everything that I’m accused of, but I don’t have anything to apologize for,” Blevins said.

On May 1, two-and-a-half months after he was elected, Blevins was sworn in at City Hall. Dozens of Enid Social Justice Committee (ESJC) members gathered outside, holding signs that read, “What happened in Charlottesville, Judd?” and chanted a riff on the hateful Unite the Right cry, “Judd, we will replace you!”

That would take time. Per Enid law, a city commissioner must serve six months before a recall petition can be filed. In the meantime, the ESJC spoke at nearly every City Council meeting. The last item on the agenda — after prayer, the pledge and a plea from the local animal shelter to adopt a pet in need, after the council addressed the mundane but essential tasks required of local governments, which recently included the reprogramming of traffic lights and a law designating size limits for pet pot-bellied pigs — is public comment. ESJC was such a constant presence that the mayor changed the time allotted for public comment on nonagenda items from three minutes to one.

Blevins’ record in the council — apart from the chaos — has been mostly without incident. He’s voted with the rest of the council, and attended veteran’s events at the base and store openings.

His hard-right posturing has won Blevins supporters who signed up for public comment to counter the “mob of weirdos and miscreants” at the ESJC and compare Blevins to venerated conservative figures like Ronald Reagan. A woman with a “Let’s Go Brandon” T-shirt beseeched the council to look inside their own hearts and ask whether their pasts included anything they “wouldn’t want known.” Another man with a long ginger beard commended Blevins for his courage in attending the Charlottesville rally, which he called a “demonstration to protect American history.”

Outside the council, too, Enid’s conservatives were rallying.

Wade Burleson, former president of the Southern Baptists of Oklahoma and a retired pastor of Enid’s largest church, was an early supporter of Blevins on Facebook. Burleson, who also sits on the faith advisory committee of the state’s controversial school Superintendent Ryan Walters, said attempts to unseat Blevins are a “race-bait trap,” an attempt by “communists” and the “mainstream media” to “divide the world over race.”

From the office of his new ministry, an old Pizza Hut remodeled by his wife, Burleson explained that Blevins’ time with white nationalism was a response to his service in the Marines and a reaction to the Black Lives Matter movement.

“He made some mistakes,” Burleson said, “but he’s not a racist.”

By the fall, organizers with the Enid Social Justice Committee were knocking on doors in Ward 1, collecting signatures. But committee members agreed they would forgo a recall if Blevins acknowledged his white nationalist activities and associations, renounce them and apologize. Blevins refused.

Behind closed doors, Enid Mayor David Mason said Blevins was more forthcoming.

“He admitted it,” said Mason, an insurance executive who was elected the same time as Blevins. Mason has a way of wearing his exasperation on his face during heated council meetings: he whips off his glasses, breathes in deeply and leans back in his swivel chair. He’s concerned about what Blevins’ ties with hate groups will do for business in a city he’s desperate to grow. “Every time you Google Enid, Oklahoma, that’s what comes up,” Mason said.

In a private meeting in November with Blevins, the city manager and the city attorney, Mason asked: “Was that you in Charlottesville? Is that you in those photographs? Did you write all those hateful text messages?”

“Yes,” Blevins said, according to Mason and the city attorney.

“Are you still involved with those groups?” Mason asked.

“I don’t have to answer that question,” Blevins replied.

“My thought,” Mason remembers, was, “You just did.”

Mason couldn’t remove Blevins, but he wanted to do something, so he wrote a measure for the next meeting’s agenda: a censure that would announce the loss of confidence in Blevins and formally repudiate white nationalism.

Meanwhile, Blevins and his supporters went on the offense.

On Nov. 12, Blevins walked into the Enid Police Department and filed a report. The brake line on his silver pickup had been cut, he said, and he offered as suspects two members of the Enid Social Justice Committee, who have denied involvement. He typed up an account of his claims on city letterhead, blaming the attack on “far left wing fringe groups.”

He went back on Jake Merrick’s radio show, where he asked the audience to pray for him and the Enid police as they investigated. Merrick described it as an “attempted murder,” a characterization that Blevins repeated at a future council meeting, in a critique of the media for its lack of coverage: “I guess attempted murder of an elected official isn’t newsworthy!”

Outside of Enid, news of the upcoming censure vote and the alleged attempt on Blevins’ life attracted the attention of Blevins’ other allies: national white supremacist groups.

Jason Kessler, a neo-Nazi and organizer of the Charlottesville rally, and Jared Taylor, a self-described “white advocate” who edits the racist website American Renaissance, came out in support of Blevins. Taylor posted a video praising Blevins as “the perfect man for the job.”

Leaders of the American Freedom Party, a white power group formed by skinheads in Southern California, had been following events in Enid closely. Back when Blevins won, the group celebrated, posting to their Telegram channels that Enid showed the political appetite for white supremacist messaging. (“Join us to run for office under a pro-White banner today!”) Now that Blevins was under threat of censure, the American Freedom Party urged its members to write to the other City Council members asking them to vote no.

One neo-Nazi blogger called the community organizers with ESJC “outrageous antifa commandos.”

The blogger wrote: “Doesn’t it feel like this could and should be used to springboard our guys into a permanent takeover of Enid, Oklahoma?”

The chamber was packed with members of the ESJC and Blevins supporters for the Nov. 21 meeting where the motion to censure Blevins would be decided. Mason, the mayor, was sure he had the votes.

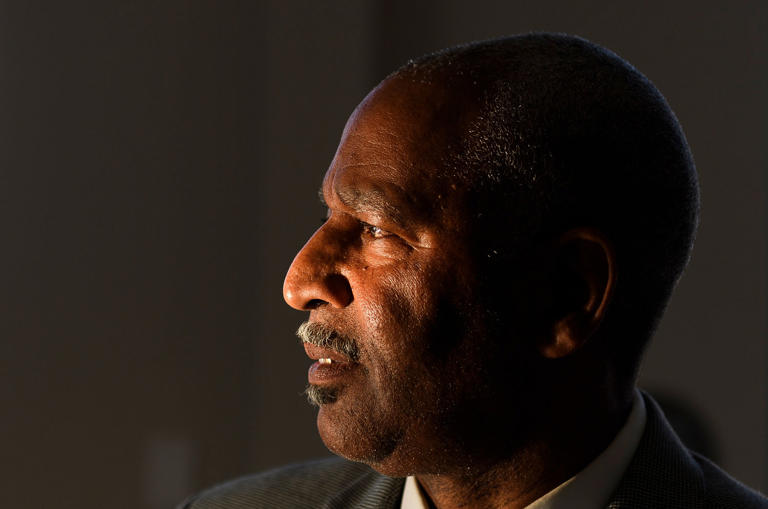

And then Derwin Norwood spoke. Norwood, the owner of a concrete business, a registered Republican and the council’s only Black member, took the floor for eight minutes. In a fiery speech that sounded at times like a sermon, Norwood told of his own experiences with racism and quoted scripture.

“We need to stop this foolishness, stop fighting, stop bickering,” Norwood said.

And then, although Blevins hadn’t directly asked for his forgiveness, Norwood was moved by the Holy Spirit to offer it. He remembers it like an out-of-body experience.

“Stand up,” Norwood told Blevins. “Do you love me?”

“Yes I do, as a brother in Christ,” Blevins replied.

“l forgive you,” Norwood said, and the men embraced to applause and groans.

With that, the votes were gone. The council voted unanimously to table the matter until after the recall election.

No one — not the mayor or Blevins or the ESJC or Norwood himself — had expected the display, photos of which led news coverage and white nationalist websites alike. Norwood knows his voice carries extra weight when the topic is racism, and he knows that his forgiveness, and that hug, might have given cover to Blevins, but he didn’t see any other way.

“A lot of people were mad at me,” Norwood said, sitting in the lobby of Enid’s new, but empty, downtown hotel. “But I’m proud of what I did. I was the example of righteousness.”

Besides, he continued, “Now no one can say that we influenced the election.”

The ESJC collected more than enough signatures and filed its petition to recall Blevins. There was still one hiccup: finding someone to replace him. They discussed supporting a progressive Democrat, but this was no time for delusions — Blevins was already sending out campaign mailers featuring pro-LGBTQ Facebook posts from Balden and Neal, the chair and vice chair, as evidence that any candidate who tried to unseat him would be a tool of the ESJC. At a City Council meeting in December, Blevins pointed his finger toward Balden and offered a warning.

“I want anybody who’s thinking about filing to understand this. You will be the social justice squad’s candidate,” he said. “You will have to campaign as this candidate in a ward that went for Donald Trump by 80%. So good luck with that.”

In January, Cheryl Patterson, 61, entered the race, a move she told friends was a result of “temporary insanity.” In announcing her campaign, the grandmother, church youth leader, former teacher and longtime Republican asked supporters not to speak negatively about Blevins. “I hope the focus will be on what each candidate has to offer & the positive things happening in Enid!” she wrote on Facebook. In interviews and at fundraisers, Patterson has repeated what’s become her unofficial campaign motto, reminiscent of Warren G. Harding’s 1920 slogan.

“We need civility,” Patterson told the News & Eagle. “Just normalcy.”

Neither Patterson nor her campaign manager responded to interview requests. People close to her said better to keep away from national news. Even offering a comment could be spun by Blevins and his supporters as collusion.

Signs for both Patterson and Blevins dot the lawns of Ward 1. Most people don’t show up to City Council meetings and haven’t been following the Blevins saga. There’s no polling in Enid, but in talking to people, those who plan to vote next month are split on who should win.

Enid Police never announced the results of the investigation into Blevins’ attempted murder claims. But in December, a month after it was opened, the police closed Blevins’ case. Members of the Enid Social Justice Committee were never interviewed. In his final report, obtained through an open records request, the investigating detective wrote that a review of hours of surveillance footage of Blevins’ truck around town showed no evidence of a crime. “The only person around the vehicle at any of the places is Judd,” the report said.

Members of the ESJC said they are aware — if not downright afraid — that Blevins’ allegations put them on the radar of Nazi groups. They’re careful about their meetings now, keeping the location secret until the last minute. On one evening this month, a few dozen members met at Jezebel’s, a tea house and event space with witchy goods like crystals and tarot cards for sale. They talked about what’s next, after they complete the mission that brought them together: a memorial plaque for a local civil rights leader, a scarf drive for Enid’s unhoused and assembling kits for people released from the Garfield County jail.

In the meantime, Balden reminded the group not to campaign for Patterson, to steer clear of Blevins’ accusations that they’re behind her run.

But they’re all holding their breath. Mayor Mason is, too.

“Hate has no place in Enid,” Mason said. “And if he were to win again, I think there will be another recall. I think it will continue until someone will beat him. We’re just not going to — that’s not us. That is not who the people of Enid are.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com

libtards love attention,jealous childish adults acting like thier in thier 20s and looking stupid to the normal people.