Bruises and broken ribs – Palestinian deaths in Israeli prisons

April 25, 2024 in News by RBN Staff

Source: BBC

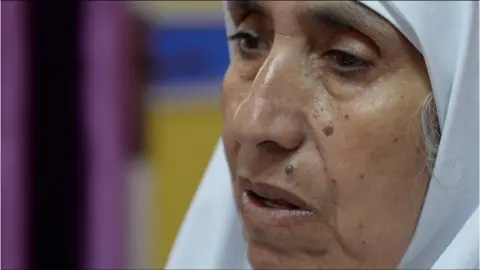

A few days after Hamas attacked Israel and war erupted in Gaza, Umm Mohamed in the occupied West Bank received a telephone call from her son in an Israeli prison.

“Pray for me mum,” Abdulrahman Mari said. “Things are getting harder here. They might not let me speak to you again”.

It would be the last time she heard his voice.

Conditions deteriorated for Palestinian prisoners in Israel after 7 October last year, when Hamas mounted its deadly assault on Israeli communities near the Gaza Strip, according to the West Bank-based Palestinian Authority’s (PA) Commission of Detainees Affairs.

Thirteen Palestinian prisoners have since died in Israeli prisons, “the majority of them as a result of beating or denial of medication”, the commission’s head, Qadoura Fares, told the BBC.

Abdulrahman was one of the first to die.

A carpenter in the village of Qarawat Bani Hassan, he had been on his way back home from work in Ramallah in February last year when he was arrested at a mobile checkpoint. He was taken into administrative detention – under which Israel can hold people indefinitely without charge – in Megiddo prison.

His brother Ibrahim said the charges against him were minor, such as taking part in protests and possessing a firearm, but said he was also accused of belonging to Hamas although there were no specific charges about any activities within the group.

Ibrahim is still trying to piece together how exactly his brother died. He has to rely on testimony from Abdulrahman’s former cellmates, as well as reports from court hearings.

One former cellmate, who spoke to the BBC on condition of anonymity, said: “After 7 October, it was total torture. They beat us for no reason, they searched us for no reason. Even if you look at someone the wrong way.”

He described having seen Abdulrahman heavily beaten in front of him and others.

“At 9am, they came into our cell, and began to beat us. One of the guards began to insult Abdulrahman’s parents, which he didn’t stand for, and he began to fight back.

“They beat him badly, and took him away to another cell upstairs for a week. During that time you could hear him crying out in pain.”

He said he had only found out about Abdulrahman’s death after he left prison a week later.

The Israeli prison service did not directly address the BBC’s questions about Abdulrahman’s death or those of the 12 other named Palestinians that the Commission of Detainees Affairs says have died, saying only: “We are not familiar with the claims described and as far as we know they are not true.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesProfessor Danny Rosin, a doctor from the group Physicians for Human Rights, attended the examination of Abdulrahman Mari’s body. His remarks corroborate what Abdulrahman’s cellmate and brother told the BBC.

Prof Rosin’s report mentioned that bruises had been seen over Abdulrahman’s left chest, and that he had several broken ribs. External bruises were also seen on the back, buttocks, left arm and thigh, as well as the right side of the head and neck with no fractures underneath.

It also quoted an additional police report which had mentioned “forceful restraint” being used on Mr Mari six days before his death.

Professor Rosin said in the report that while no specific cause of death had been found, “one may assume that the violence he suffered manifested by the multiple bruises and multiple severe rib fractures contributed to his death”.

He also added that “irregular pulse” or a “heart attack” could result from these injuries without leaving any physical evidence.

Israel currently holds more than 9,300 security prisoners, the vast majority of whom are Palestinians according to the Israeli rights group HaMoked, including more than 3,600 people in administrative detention.

These figures do not include detainees from the Gaza Strip being held in separate facilities by the Israeli military.

Mr Qadoura says the change after 7 October “affected every aspect of the prisoners’ lives”, alleging that prisoners have been subjected to starvation and thirst and some of those with chronic illnesses were denied their medication. Beatings became more regular and more brutal.

“I met a detainee who’d lost 20kg in the last three months,” he said.

“It’s as if the war on Gaza was also a war on Palestinian prisoners. It was all a form of revenge.”

The BBC has previously heard from Palestinian prisoners who described being hit with sticks, having muzzled dogs set on them and having their clothes, food and blankets taken away in the weeks after 7 October.

The Israeli prison service has denied any mistreatment, saying that “all prisoners are held in accordance with the law while respecting their basic rights and under the supervision of a professional and skilled prison staff”.

It said prisons had gone into “emergency mode” after war broke out and it had been “decided to reduce the living conditions of the security prisoners”. Examples it gave included removing electrical equipment and cutting electricity to cells and reducing prisoners’ activities in the wings.

In the West Bank village of Beit Sira, Arafat Hamdan’s father showed where Israeli police officers had kicked the door of his family home and stormed in at 04:00 on 22 October looking for his son.

Police covered his son’s face with a thick black cloth and closed it around his neck with a rope. The mask smelled strongly, he said, and Arafat clearly had a hard time breathing with it on.

“I kept trying to comfort him.” Yasser Hamdan told the BBC. “It’s ok. They have nothing against you. They have nothing against us. I kept telling him that as they tied him up outside the house. Then they took him.”

Two days later a phone call came. Arafat had been found dead in his cell in Ofer prison in the West Bank.

Israeli authorities have not explained how he died. Arafat had Type 1 diabetes and would suffer from low blood sugar levels from time to time.

His father said one of the police officers arresting Arafat had told him to bring medicine with him, but it was unclear if he had been able to.

The BBC obtained a report by Dr Daniel Solomon, a surgeon who was present at the post mortem of Arafat Hamdan at the request of Physicians for Human Rights.

Dr Solomon said it had been carried out in Israel on 31 October but added that the condition of the body, due to prolonged refrigeration, had made it harder to determine the cause of death.

He also noted the absence of any records showing if Arafat’s diabetes medication had been administered and at what dosing.

The report also mentioned the need for other tests beyond the post mortem to determine the cause of death.

“Until now we don’t know how he died. Nothing is clear.” Yasser Hamdan said.

Neither Arafat’s nor Abdulrahman’s bodies have yet been returned. Their families want to arrange their own post mortems, hold funerals, and say a final goodbye.

“He was my flesh and blood. Then he was gone in a moment,” Yasser Hamdan said. Photos of his son were everywhere you looked in his apartment.

Umm Mohamed showed photos of Abdulrahman on her phone, pointing to one and saying: “Look at him. He was so cheerful.”

Over time he had become a leader in his group of prisoners, she said.

“He’d call me when he was making breakfast for them when they were all still asleep. He was always the most active. He would never sit still, that boy.”

She broke down. “Bring him back to me. I want to see him one last time. One last look.”